The Portable Promised Land Read online

Page 16

“Lucid! Phone call!” This time it was real. As the cop led me away, Louis M. Armstrong called out, “Lucid! Is you Black?”

And I really didn’t know what to say.

When I got upstairs they pointed me to a phone. “Are you okay, J?” It was Christie from our lawyer Morris Cochran’s office.

“Yeah, I guess. Where’s Mo?”

“J, he’s gone. He took off sometime yesterday.”

“What?”

“We don’t know where he is. The office is in a state of panic.”

“Wow.”

“And you’re broke.”

“Wh —”

“Mo.”

“No.”

“He cleaned you out.”

“So who bailed me out?”

“The Black Widow.”

I died a little bit then. The Black Widow was the sort of person who felt like if you owed her she owned you. I’d heard her talk about men who owed her money. She said she let them clear their debt by fighting, as in, human cockfighting. But they always stopped the fight before someone got killed. That way the loser had to walk around knowing people saw him get his ass beat.

“She says you should come to Brooklyn right away. She left a plane ticket for you.”

“Where’s my brother?”

“They let him out first. He wouldn’t wait for you.” I flew home alone.

“Those crackas wanted to hang yo Black ass!” The Black Widow said. We were in a small room on the top floor of her apartment, the walls painted black, the lights dim, her homegirls seated around the room, staring at me like a captured enemy. She’d been yelling at me without stopping for so long I’d forgotten the sound of my voice. “And they knew they could get away with it! They had you on breaking and entering, drug possession, gun possession. You really put yourself out there, J-Love! You know how much it cost to get a nigga out the hands of a lynch mob?”

She paused. “It’s a damn shame,” she said, “that Cornbread ain’t tell you to look out for lynch mobs.”

I felt smaller than a pin. A giant Black Widow thumb blackening the sky above me. She’d met Cornbread just hours before through a friend of a friend from the Black prep-school circuit.

“I always thought y’all were a little strange. So you’re broke and if you admit your little charade your career is over. You owe me for bail, for record sales that I’ve lost because of your little televised gun battle, for keeping my mouth shut about your little secret. And you’re broke. So you have a bill you can’t settle. I think you know how we settle bills around here.”

“You’re not serious. There has to be another way.” I begged like I’d never heard of dignity. “Pleeeeease!” They ripped me from my knees and moved me like a prisoner down the stairs and around the corner to the bodega.

Some blazing salsa filled the front room, a flurry of fast and sharp trumpet notes flying through the air. As The Black Widow stormed through, everyone scrambled out of her way. She moved straight to the back door.

Beyond the door was a place so completely unsuggested by the previous room that I felt I was stepping into an alternate universe. There were wooden bleachers filled with rowdy old Latino men and a cage large enough for two to stand in. The Black Widow grabbed the back of my neck. “Your bill is too large for the regular shit.” A blindfold was pulled over my head and strapped on tight. I couldn’t see a thing. I was pushed forward and walked. I felt steel squares beneath my feet and guessed I was inside the cage. I heard the cage door slam shut and went rigid with fear. I heard someone breathing hard. I needed Dice.

I moved cautiously toward the breathing. Then out of nowhere my head snapped back and my eye filled with pain. The crowd ooohhhhed! and I fell back against the cage’s wall. I jabbed twice, finding air. Then my stomach absorbed a punch and I hit the ground hard, my chest instantly tattooed by the cage floor. “Papi!” someone screamed. “You een for eet now!” A heel slammed into the middle of my back and then again, as if trying to force my spine toward the front of my body. I rolled over and reached out, then found my ribs bookended by knees. He was sitting on top of me. Blows rained on my face. I felt teeth being knocked loose and blood flowing freely from my nose. The blows were coming too quick to block. It was pain like I’d never known, intense and blinding. My blindfold fell off and I opened my one working eye a slit. Atop me was Dice. I saw him pull his fist behind his shoulder. Straight toward my good eye it flew. I heard a loud ring, then the pain just stopped.

I saw my obit in the newspaper today. It said, “James Marlon Lucid, an African-American record executive who created a multi-million-dollar record company in less than a year and helped usher in a new level of racial tension in America with the strange hit song “He’ll Die, Too” by The Black Widow, died Friday morning at Brooklyn General Hospital. He was nineteen.”

They say history is written by the victors. They say if you tell a lie enough it becomes the truth. They say I’m Black. And, being dead, there’s nothing I can say about it.

ONCE AN OREO, ALWAYS AN OREO

The Black Widow Finale

Once upon a time, early in the new millennium, long before German, Brazilian, and hard-core Nigerian MCs ruled hiphop, there was a woman called The Black Widow, the baddest thing hiphop had ever seen. She sold records, she destroyed clubs, she brought that revolutionary impulse once so critical to this culture to the minds of the masses. She roared into the American consciousness with the sort of loud, searing blast you get from standing beside the speakers when that first Goliath sound comes shooting out. She had the world talking about when the American Race War would happen. Not if. When. Your position on that imagined war defined you in her era as much as people’s positions on abortion or affirmative action or marijuana legalization had defined them in earlier times. And in the same way the sound from a concert hangs onto the tip of your ears, ringing all night long as you drive home, undress, fall asleep, and wake up the next day, The Black Widow kept on ringing in the collective American ear long after that first blast.

But her first and only album, the masterful You Are Who You Kill, set forth a strange series of events: she was tried and acquitted on charges of obscenity and murder because of the album’s interludes (actual recordings of people being killed). Then a teenage Black girl, inspired by The Black Widow’s music, shot and killed her white boyfriend and then herself live on MTV. Then, J-Love Lucid, one of the teenage millionaire twin brothers who discovered and signed her, was beaten to death. His brother, Sugar Dice, was charged with the crime, but ultimately acquitted. And then a reporter from the Village Voice discovered The Black Widow had completely fabricated her background. Isis Jackson was not a Black Panther’s daughter raised with the story of Nat Turner as a bedtime tale and had not robbed drug dealers to make a living. She was the seed of a Black lawyer named Morris Cochran and a Jewish actress who’d once had a speaking line in a Woody Allen picture. Before her rap career Isis had attended one of Manhattan’s most exclusive prep schools. Fellow students said, “She was always good at drama.” Isis disappeared as fast as she’d arrived, leaving no forwarding address.

I was the first to do a major story on The Black Widow (for the Source way back in 1999, an introduction so shocking that many refused to believe she existed). One day six months ago I woke up and had to know what had happened to her. She had been everything hiphop could be all at once: over-the-top and from the heart and brilliant and revolutionary and hopeful and nihilistic and macho and racist and hypocritical and cartoonish and way too real. Epic theater worthy of Shakespeare, costarring musical anarchy, disinformation, deep truth, organized chaos, gleeful malevolence, and wild mythomania. I knew only that she had ended all contact with her family and moved to LA. I set out to do a fun where-are-they-now piece. I had begun a piece that would break my heart. The last hiphop piece I would ever do.

It took a month of calling and snooping — starting with LA’s activist community and the underground hiphop scene, then the cult churches and t

he strip joints, then the drug underground and the jails and the morgues. I finally found her, four days before Christmas, almost eight years into the new millennium, in the George B. and Dr. Meika T. Kinkaid Center for Racialized Psychopathology at the University of California at Los Angeles.

The Kink is home to the nation’s only race disorders clinic. It’s little more than a humble two-floor building with tiny dorm rooms for thirty clients, a few televisions, a cafeteria, and a ping-pong table. The atmosphere effects a sortof emotional padding, like the gay softness of kindergarten: the walls are a bright lime green, a shade that seems to say, “Get happy, please.” Pieces of colored paper are taped up with happy little quotes — “If you’re gonna walk on thin ice, you might as well dance.” — Jessie Winchester. “Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long shot.”— Charles Chaplin. “The good news is nothing icky lasts forever.”— Deborah Norville. But the two doors to the outside are locked at all times and marked with signs that say in large letters, “Elopement Precaution!” The cheery overtone of the pseudopenitentiary mocks the severity of the psychoses being treated and makes the place kindof creepy. It’s the sort of place that’s clean, but makes you want to shower once you leave.

The Kink’s thirty clients are people of all races, defined as “those for whom a certain sort of race-based hatred, including hatred of self, has impaired their ability to live.” They are all sorts of freaks from beyond the fringes of sanity, and yet, such is the tricky nature of racial psychopathology, they are people you would meet, or work with, or live beside, and think, here’s a normal person. They are segregationists, race chauvinists, Negro-phobes, caucaphobes, wiggers, anti-Semites, serial gay bashers, professional church burners, actor Blair Underwood. A Black woman confined to her home for years with severe agoraphobia because the chronic reporting of Black crime, she feared, was the orchestrated prelude for martial law. An Asian woman who’d been a leading bank executive until she developed a tactile delirium that drove her to obsessively scrub her hands every time she met a Jewish person. A Black man with oedipal conflicts so twisted he could only achieve orgasm with women who were mothers. And with the children watching. A white man who’d hardly slept in years because of a simultaneous fear and hope that a Black man would break into his apartment and rape him. A white woman who believed she was the reincarnated soul of Aunt Jemima.

The goal of the Kink is to quiet the mind by repairing superego defects and promoting personality changes by helping clients see the irrelevance of race and obliterating the concept of one race’s superiority. Treatments include hypnotherapy, psycho-drama (role-playing), hierarchy reconstruction, and free association, as well as a variety of drugs, including Zoloft, Prozac, Elavil, Librium, Valium, Xanax, Thorazine, Clorzaril, and Risperdal. As well, the Kink attempts to create a world where race is completely nonexistent. Everything down to meals are edited for racial overtones: there is never fried chicken or spaghetti or egg foo yung or sauerkraut served in the Kink Center. Only culturally generic foods, like, say, baked chicken and beans. When I found Isis she was at lunch, sitting over a bowl of tomato rice soup, a hot dog on a bun, and baked beans.

Hard rain pattered the windows like quick drumbeats. I noticed this only because Isis, who once overflowed with thought and fire, now spoke in short belches separated by long pauses, her sentences begun and then subsumed by silence, some of them completed, many abandoned. The Gucci she once wore was replaced by a loose, blue cotton sweatsuit, her breathtaking body shrunken into something thin, boxy, and waifish. The woman who roared through Brooklyn in a canary-yellow Range Rover lived in an eight by six foot room with a handwritten sign taped to the door that read, “Isis J.”

“They’ve increased my medication three milligrams....” she said, then drifted back into silence. Picked at her food. Shivered a bit.

“How do you feel?” I said.

“I am...se- da-ted.” And back to silence, long and awkward. She looked right at me and I felt she wasn’t paying attention to me. I felt she was vanishing right in front of me.

“I met you before?” she asked.

“I interviewed you for the Source when your album came out.”

“Got weed?” she said. “I used to hear brain cells pop with each puff.” She laughed.

“I’ll bring some tomorrow,” I whispered.

“Might not be here tomorrow,” she whispered.

Just then, a Black man a few feet away leapt up from his chair, hot dog in hand, flapping his arms, screaming at no one in particular, “I ain’t Black!! You ain’t Black!!” Three linebacker-sized staff members rushed in and tackled him hard. They stuffed him into a straitjacket and carted him off as he screamed, “No one is Black! We all are!” In the commotion Isis walked off to her room. Later I found a nurse who would tell me about Isis’s condition as long as I didn’t use her name.

“Isis admitted herself to the Center about a year ago after a nervous breakdown. She was diagnosed as having split-personality disorder complicated by Black Napoléon Complex. Napoléon’s is caused by a lack of melanin and / or a privileged-class up-bringing that spurs on feelings of cultural inadequacy, or inferiority to other Blacks. The client acts out, using politics as a shield for extremely low self-esteem.

“Isis grew up on Park Avenue in New York City, attending New York’s best private schools. A traumatic incident heightened her fixation on the ways she was different from other Black people and led her to believe that her inner child was actually a meek white girl. In layman’s terms, she believed herself an oreo.”

The incident, the nurse explained, was one of those formative childhood experiences that high school is famous for. One of those moments when one finds out exactly what the peer group thinks of her and walks away permanently scarred.

It happened one night at a school dance. Though there were very few Black students at Riverdale Country Day School, there was constant conflict between the scholarship kids and the non-scholarship ones, a worded and wordless ongoing debate about who is Black and what Blackness means. This was a battle for territory, for the right to define the truth, and it was fought viciously. This night the battle reached a fever pitch when the DJ spun from a Snoop Dogg jam into a Digable Planets record, and the dance floor’s Black constituency turned over completely. Then Johnfkennedy Jackson, one of the scholarship boys, stepped into the dancing circle, and with the entire class looking on, he screamed, “Them Digable Faggots ain’t Black and,” turning to Isis, cocking the gun that was his mouth, “neither is you. You ain’t Black!”

“It was,” the nurse said, “for a fifteen-year-old, devastating. In drama class she had created a character — revolutionary, ultra-Black, powerful — called The Black Widow, and now she embraced the character as psychic armor. One day she stepped into character and never stepped out. Her life became a twenty-four-seven theater piece.

“But when the persona began to have serious repercussions — the girl who killed herself, the manager who was murdered, and especially the public embarrassment of being discovered a fake — she ran from it. But that secondary persona had displaced the original so completely that she was left with no understanding of how to relate to the world, as if she could no longer recall who she was in the first place.”

Despite years of selling the world on her own intense ultra-Blackness, she never quite managed to convince herself. Once a fat girl, always a fat girl, prep-school girls used to say. For Isis it was the same — she had believed she was an oreo and tried to change that, but deep down she knew that no amount of chocolate gobbed on top could change the fact that there was flaky white crust at the core. Once an oreo, always an oreo.

I went to Isis’s room to say goodbye until tomorrow. The door was closed. I could hear a phone doing its off-the-hook screech. She was on the ground, arms out and limp. On the floor beside her was a rainbow of pills — orange, yellow, white, sky blue, pink, brown, and all sorts of beige. She looked as if she were sleeping, except that the color was al

ready draining from her. I said nothing, just stood in the doorway staring at her, her bluish lips, her stiff open eyes, her mouth bent into a slight smirk despite the yellow foam oozing from one corner. The receiver was by her head, ranting in rhythm. It was as if she’d swallowed, reconsidered, leaned from the bed, grabbed for the phone, fallen, then embraced her self-delivered fate and met it with a semismile. The smell of death wasn’t yet in the air, though the feeling that death was in the room was strong.

I stood in the doorway a long time, staring, too shocked to move or cry or do anything. This wasn’t how the story was supposed to end. This was a girl who’d represented hiphop completely. She was hiphop. So if hiphop could die, how could I continue to live in hiphop, a world that, like marriage, either leaves you very happy or completely heartbroken, and probably both, and one way or another delivers you directly to the grave?

THE COMMERCIAL CHANNEL: A UNIQUE BUSINESS OPPORTUNITY

By Jack Lucid

CONFIDENTIAL

“Commercials have become little films.”

—a Clio-winning ad executive

PART I: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

(AN ANALYSIS OF THE MODERN TELEVISION INDUSTRY)

The television industry is at a crossroads. The intense knowledgeability of the increasingly cynical modern audience — deluged by insider news from sources such as Entertainment Tonight and the self-referentialism apparent all over the dial — has made it increasingly difficult for that audience to establish a visceral relationship with characters. Instead, they see actors acting and calculate how much they are making per week considering the exorbitant weekly salary they held out for last fall. Or perhaps they’re looking closely at how actress X is dealing with guest actor Y who just finished a film where he was widely rumored to be having a tryst with actor Z who is actress X’s husband or son’s father or whatever. In short, the illusion of reality has been shattered by the backstage pass television has offered on itself. Moreover, reality shows and game shows have made the experience of being on television ubiquitous and quotidian. Those reality-based shows in which real people are thrown into completely surreal situations have opened the opportunity to appear on television to any and everyone. It is no longer a special thing to be on television. The question that audiences from Bangor to Spokane are asking each other is, When is your turn?

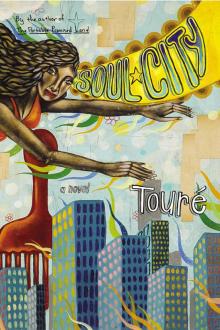

Soul City

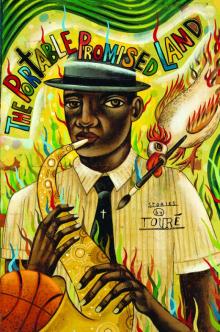

Soul City The Portable Promised Land

The Portable Promised Land